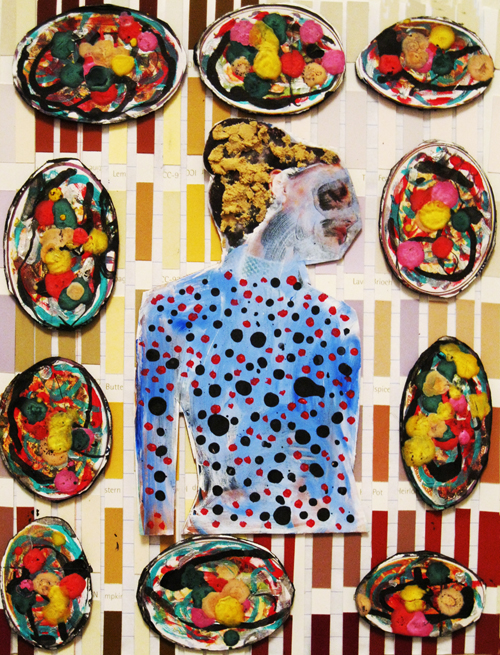

by Daria Booth

Pomegranate

Punica Granatum. Chinese Apple. Ancient fruit. Superfood. Pomegranate. Darlings of the small plate crowd—sprinkle the seeds on your chic beet salad. The juice improves erections in men with erectile dysfunction. Christians see pomegranates as a symbol of Jesus’ resurrection. In Jewish tradition, it is a symbol of righteousness. There are supposedly 613 seeds in each fruit, the number of commandments in the Torah. Pomegranates were Persephone’s favorite snack during her visit to the underworld. Delectation, erection, resurrection—these are the superpowers of this righteous and mythological fruit.

All alone in my kitchen, bored and putting off other more important tasks, I roll a pomegranate on the counter as I pull the garbage pail out from under the sink. I bite into, and then with my hands tear open the leathery red skin, exposing the umbrels of tiny areoles of juice. The clusters of clear red juice jewels are shiny and make my mouth water. Standing over the kitchen garbage pail, feet spread apart for stability, face parallel to the top of the trash, I shamelessly and with great abandon, bite into the red seeds, squeezing them in my mouth, extracting the tart, staining juices, some dripping down my chin.

Not very delicately, I spit a wad of spent seeds into the trash, and wipe my chin with a slightly musty dishtowel I grab from the counter, all while standing over the trash. I bend over and take another, bigger, chipmunk-cheek-sized bite. My eyes are closed. For just a moment, I wonder why I am eating the pomegranate this way; it is not a regular practice. I am alone and unseen. No one comes by, no other adults live here; I can do whatever I want to do. I pick at my toenails, I walk around naked, and I eat pomegranates as if no one is watching, because no one is watching.

Again, I squeeze the seeds in my mouth and swallow the erecting, resurrecting, delectable juice. Engaging my tongue, teeth, cheeks, and nose, I imagine I am in a giant vat of pomegranate juice gulping it down as I swim. I cannot get enough of the stuff. When all that is left is the nutty tasting used-up seeds, packed in the side of my cheek, I lean closer to the trash and dispense them, in three big chunks on top of the previously spitted seeds. As I grab for the dishtowel I feel someone watching me, the same way you feel when the person in the next car catches you in the middle of any manner of private, personal grooming.

A man is standing at the door to the kitchen, which is glass of course, providing an unobstructed view of my private pomegranate activity. I wipe my chin and laugh, “Just a minute.” The fellow remains expressionless. I open the door and he hands me a form on a board, “Sign here, please.” I sign, he hands me a package. Apparently we are not going to discuss what I was doing, or even have meaningless banter to be polite. Just as well. I go to the bathroom to wash my stained hands, and see the pomegranate juice stains on my chin and down my neck, not unlike a Maori tattoo, but pink. I am alone again. I wonder if he will tell anyone about me.

The White Food People

Driving to Richmond from San Francisco, it feels like we are going 500 miles out of town, but it is really only about twenty. We are on our way to a small dinner party at the home of friends who just had a baby. They are my boyfriend’s friends, not mine. I tell him not to say anything too weird, like their baby looks like a duck. He did say that once on the way to another dinner. All of our friends are getting married and having babies. We are not. It feels like we are aliens, travelling from the city planet of San Francisco, to the foreign soil of suburbia.

The table is set with tasteful white plates from Crate and Barrel, a wedding present, and white, cloth napkins, also a wedding present. The dad has made the meal because he is an evolved dad, who helps equally with everything. If he could nurse the baby, he would. The first course is cream of cauliflower soup. I look down at the white tureen at my place. It contains hot, white liquid with some white lumps floating in the center. There is no differentiation between the edge of the bowl and the surface of soup. It blends into the white tablecloth, like a meal in limbo. I look up to see my boyfriend looking at me. He knows I do not like white soup. I cannot tell if his look is sympathetic or amused.

Next is the main course; a chicken dish in a white, creamy sauce. Some version of Chicken Á La King, which I had always thought was a joke recipe. There is white bread, and white wine, which is yellow, thank God.

I excuse myself and the mom directs me to the bathroom in their bedroom. In the city, our railroad flat, one room leading to another, a view of the freeway and the Coca-Cola sign near the on-ramp, is so different from this house. I enter the bathroom off the master bedroom. Closing the door, I lift my shirt to see long, angry red welts on my middle, like alien critters are under my skin. The white food is giving me hives.

In the mirror’s reflection I notice a freshly cleaned diaphragm proudly sitting on the edge of the tub. They are having sex again, good for them. I wonder if the mom wanted us to know, or if the birth control device by the tub is an oversight. I feel embarrassed at having seen it, and prudish, especially since I am alone. I wish we could leave.

Dessert is the dad’s specialty. Something German: a white sponge cake with a hot white sauce. The meal ends as it began, in limbo. I take a polite bite. The hives are spreading to my arms.

After dessert, the dad has something special he wants to share with everyone at the dinner table. He goes to the refrigerator (white) and retrieves a round, Tupperware bowl from the freezer. He opens it and proudly shows us the frozen placenta and afterbirth, the leftovers from their child’s birth. It is red with ice crystals and looks like frozen Spaghetti-o’s. I look at the mom; she is busy adoring her husband. Steam from the hot white dessert hits my nose and I feel ill. The dad invites us to help him plant a small tree in the yard. He wants to bury the placenta and birth sauce at the base of the tree. He says it’s a ritual, it gives the mother closure. He says returning the remains to mother earth celebrates life. I don’t feel celebratory about this. I have seen too many things tonight that came out of the mom’s vagina. I wonder, when they tell their kid about this, if she will want to try to dig it up—I would.

The baby, vagina item #3, wakes up finally and grants an audience. She is tiny, pink, squalling, and alien. You must hold her, the mom insists. I fear the hives are showing on my neck and my ears feel hot. She hands over the swaddled baby. She is so new; she looks larval. The dad and men guests have dug a hole and are ready to plant the tree with the placenta. The women watch through the sliding glass door. It is still frozen, so it plunks out of the Tupperware as a whole piece. This is a blessing.

In the car on the way back, we are silent, holding our breath, until the Bay Bridge lands us safely back to our home planet.

Cheesecake

You know you’re going to eat the cheesecake. It’s in the refrigerator on the plate covered with plastic, just a few slices missing, waiting. Waiting for you. It knows, and you know, it’s just a question of time. You could have given it away to the dinner guests to take home, but you quickly and surreptitiously put it in the refrigerator while they were putting on their coats, and saying their goodbyes. You never mentioned it again. You let it rest in the refrigerator all night. You ate a soft-boiled egg at 7:05 a.m. with a piece of toast—Sara Lee 45 calorie whole wheat bread—and you felt virtuous. You saw the cheesecake out of the corner of your eye, it looked back, and you think you saw it wink. It probably did. You think, “I’ll take my vitamins,” since they make you feel a little barfy, and then you won’t want any cheesecake.

You know you’re going to eat some before this day is through, but first you must play this game.

It calls your name while you’re folding the laundry, and you ignore it by making the most precise towel folds of your life. Martha Stewart would be jealous of the towels you just stacked up, all of the folds facing the same way. Still, your feet turn towards the kitchen and, zombie-like, you take a glass out of the cabinet and fill it with water. You drink the full glass of water and slosh away from the refrigerator before its tentacles pull you in and force you to open its door. Out of view of the beast, you are safer, but part of you knows full well that you will be slicing a sliver of cheesecake and eating it off the knife. Maybe not right this minute, but soon. You know this, like you know you will not answer the phone when your mother calls, like you know you will pretend you don’t see that acquaintance at the grocery store that you don’t want to talk to, like you know you will re-gift jars of jam given to you by well-meaning friends at the holidays.

You also know you must stave off the cheesecake for an appropriate amount of time; enough time so you can feel you tried and only just gave in after a hard fought struggle. You know it’s not true, but you pretend to believe that it’s better if you make yourself wait longer. Trying is good enough—no one follows through on anything anymore.

You pick up the newspaper and start reading the style section because the clothes ads will help you ignore the taunting of cheesecake. But it’s too strong. Bastard. It knows you better than you know yourself.

You go to the cabinet, you pull out a plate and let it clank down on the counter. You fling open the refrigerator with a fierce pull on the handle and a devil-may-care attitude. You pull off the plastic wrap and lick off a shmear of cheesecake. No reason to waste good cheesecake. You hold the knife over a section for a slice about four inches, then you edge the knife in for a three inch piece, then out again to four, then back to three, and then more like a two and half inch piece, and you cut. You put it on the plate and then go back to the cake and cut off the one and half-inch sliver and eat it off the knife. You glance over at the kitchen door to make sure no one’s there. This is a private moment.

One time you stole a box of Twinkies from your grandmother’s pantry, and hid in her coat closet with the box. Your mother didn’t allow any Hostess snacks at home. You ate them all, five or six individually wrapped Twinkies. They were sweet but had no real flavor. You hid the wrappers and box in the back of the closet. This was a private moment. Later, your grandmother found the box and wrappers. You lied and said you didn’t take them. You were sent upstairs to the bedroom for lying. No one asked why you ate the Twinkies. You still don’t know why.

You and your slice of cheesecake breeze over to the couch, as if this one little slice will do you and you’ll not have even a crumb more. You flip on the television to watch something mindless. You think you’ll savor this piece of cheesecake, and plan to eat each bite slowly, in fact, you vow not to eat any during commercials. A solid plan. In the next moment you look down at the plate and it is empty. You look at the fork accusingly, although you know you just ate the whole piece in less than a minute. You think you hear the refrigerator giggling in the background, so you shoot it a dirty look. Now it’s a muffled giggle. What a bitchy appliance.

You flip channels all the way through all the ones you get, once, twice, three times. You leave it on Dr. Oz who is talking about fiber and demonstrating how your bowel works with a giant model of a bowel and rectum, made from balloons and sponges. You go to the fridge and take the plate with the rest of the cheesecake and sit back down with the fork. You feel bad. You want it. You feel bad. You still want it. You take a little bite, and then another. You attack it with your finger and eat a chunk this way, forgoing the fork.

You feel full and empty. You shove it down, that edge of uncomfortable feeling. Sad? You don’t know. It retreats. You manage to stave it off again. You feel relieved and anxious.

You hear a car pulling into the driveway, so you run to the trash and dump the evidence, placing a paper towel on top, so it won’t show.

It’s just the neighbor. You think about taking the cheesecake out of the trash. You don’t. You can draw the line, you think.

Daria Booth writes flash nonfiction and personal essays, and creates illustrations and cartoon art. She completed her MA in English from Chico State in 2017. She lives in Paradise with her spouse Alan, dog George, and cats Milo and Flour.