By LaToya Watkins

I ain’t miss them kids much last night, but I wish I did. Feel like it’ll be right if I try to feel something for them. Like I’m supposed to, but I can’t. I watch them chase each other across the tall grass and try to remember playing in the yard when I was little. I shouldn’t. Me being little too far away and too hard to think about. I shake my head like that’ll make me stop catching pieces of the past in my mind. I been sitting in my car for about fifteen minutes. The kids don’t see me, and I don’t know why they don’t. I’m parked close enough till they should’ve done recognized my car. Just a couple of houses away. If they was looking for me, they’d have done seen me. The boy look like my momma. Got the same cinnamon skin and gold hair. The girl the spitting image of her own momma. Her mouth is firing off just like her momma’s, and her white teeth look funny against her dark skin. Just like her momma’s used to. I ought to feel bad about they pants being too little, but I don’t. I don’t even wish I had gave they momma the extra money she asked me for a few months ago. Said she needed to buy them new winter coats and gloves. I lied, and I don’t feel bad at all. Not even sitting here looking at the boy’s jacket, sleeves too short to cover his arms all the way, make me regret lying to her—telling her I ain’t have no extra twenty-five dollars.

Fore letting myself up from the leaning car seat, I look back at the trash bags in my backseat. I shake my head and lean over and open the glove box, moving my finger around until I feel the button that opens the trunk. I feel like I done loss when I hit the button. I wish it was another way, but I know I got to do it.

The kids’ momma, Teniola, was boiling water while I was trying to forget about work yesterday. I heard the water falling from the faucet into the stainless steel stockpot and her mumbling under her breath. She don’t like boiling water, but she done made herself think she got to. Somebody told her the water got fluoride in it. Somebody else told her fluoride bad for us. And somebody on top of that told her fluoride the first step in some new world order type of thing. She got it in head that boiling water make the fluoride disappear. Said she saving the world from the anti-Christ.

Watching them kids out there doing all that running and playing make me wonder what her boiling water must be like for them. I just stand there for a minute and look at how free they is. I wonder if they worried about the fluoride and public school and Jesus like they momma. They don’t see me at first, but then the girl giggle and her head kind of turn toward me. I been made, but I still make my way to the back of the car.

I make my way to that trunk thinking about how they supposed to get something out of my being around. Be protected from they momma’s crazy ass or something, I guess. My daddy left me with my crazy-ass momma fore I was old enough to know his face, and I always kind of thought if he’d of been there she wouldn’t have hated me so much. I’d have been protected. That’s what daddies supposed to do, I think. Just be there to make sure the momma don’t lose her shit. My momma didn’t boil water, but she was a beast with belts and extension cords and cigarettes. To tell the truth, I don’t know what Teniola like when we have nights like last night—nights when I leave them alone with her.

“How were things at work today, Rutherford?” Teniola asked me yesterday. I knew that was really just her bridge into conversation with me. She wanted something—she had to. It’s the only time she ever even talk to me. I ain’t worth nothing to her cause I don’t write the government checks for childcare, rent, food and the kids’ Medicaid each month. Uncle Sam do all that. If he—Uncle Sam—was the man coming home to her every day, I bet he could get a cold beer and a fuck without saying a word.

“Fine, Teniola. My day was fine,” I lied to her. I wanted to tell her that the boss made me the head forklift operator and let three other dudes go. Fucked me up. I was happy for me and sad for them at the same damn time. All three dudes from our side of town—the hood. They got kids and girls and don’t want to end up in the pen, so they hide behind forklifts and big boxes or wooden bed-slats loaded with shit they’ll never see outside of the boxes or plastic. They all men like me. Men who done time and don’t want to do no more, so they work hard for almost nothing. But Teniola didn’t want to know that. She wanted fine, so I gave it to her.

She let out a long, deep grunt and I knew she was struggling to get the pot over to the stove. I knew this without even turning around to look at her. Teniola a little woman. Not no dwarf or midget or nothing. Just little and petite. That’s what drew me to her ten years ago. Something about that was different in our hood, where all the women fat and mad at men. That’s how she caught my attention. Just being small and smiling with them pretty white teeth against that smooth dark skin. She was a student at South Plains College. She was trying to make it out of our West Texas trap town. I thought I fell in love with her for that. Now I don’t think I know what love is.

“You think Mr. Dickson got a few more of those desks to donate?” she asked.

I exhaled and rolled my eyes, and then coughed to cover the exhale. I was glad she couldn’t see the look that was probably on my face. My man-couch sit up against the wall beneath the bar. She couldn’t see me. She can’t never really see me.

I like things where I don’t have to look at Teniola. She used to be something to look at before she went to that quack dentist who told her that if she didn’t allow him to pull all her teeth on the count of some gum disease, she’d die. After losing all them pretty white teeth, she started losing weight. Her quack doctor, who I was sure was connected to the quack dentist, said some of the disease had already reached her bloodstream and what was going on with her appetite and weight loss was because of her teeth. Ain’t got no money to get no bridge or nothing, so she just stuck being skinny and ugly. She twenty-eight but look seventy, maybe even older than that. Sometimes I can’t stand her she so ugly, but I hate pissing her off. To be so small, her steam get hot.

“I only ask,” she began, “Because Adonis, Tyrus and Cynthia’s son, will be starting with us next week. We only have five desks. Adonis makes six students.”

I picked up the bottle of beer from the end table, knowing she was staring straight through my skull from the other side of the bar. I was trying her patience. I knew it. But she needed that desk. Kind of made me mad that she only needed me cause of a desk. A man need to feel needed, but not just cause of no desk.

I like to see the panic in her eyes when she think I’m leaving. Like once a year, when the housing authority lady came to inspect the house. Come to make sure ain’t no men living there. I pack all my stuff up in black trash bags and haul them out to my 1987 Cutlass Supreme. I stuff the bags in the trunk—everything I own—and act like I’m real upset that I got to hide my stuff so she don’t lose the house. Her lips go to quivering, and them eyes go to watering, and she go to making promises she know she can’t keep. Deep down inside, though, I feel glad somebody want me bad enough to cry for me.

“Daddy?” the little girl call out to me when I get out and make my way around to the trunk of the car. She don’t come running toward me or nothing like that. She four. She at the age where she ought to run up and hug me. Ought to be all happy because ain’t nobody better than her daddy. But she just stand there in the yard, watching me. The boy stop playing too. Like his sister, he stand froze. He ain’t four like her. He eight. That ain’t no running-to-your-daddy age, but he didn’t run to me when he was her age.

Both of them just stand there together. I know they don’t know what to do cause I ain’t never really known what to do when it come to them.

“Yeah, baby girl. It’s your daddy,” I say, but I say it real low. I know they can’t hear me. I don’t think I want them to.

I pull the trunk open and stand there looking inside it. I feel weak and then dizzy. I want to throw up. This feel like death. Like I’m killing myself. I feel like I don’t ever really win nothing. Losing all I know.

I look back at the kids. The little girl coming toward me slow like a sneaky cat.

“Daddy, what you got?” she ask, still slow-stepping to my car.

The boy saying something to her, I think. He whispering, so I can’t hear him, but he gritting his teeth and she pretending she can’t hear him. She keep to me.

It make me feel bad for her. She want to love me like a daughter love a daddy, but we ain’t gone never be like that. It make me feel bad for him too. He gone hate me. He gone hate me just like I hate my father. He gone hate me cause he don’t know me. I don’t want it to be like that. I wish I could go back and change the kind of daddy I been to him, so he don’t be the type of man I am. A man that want to be a man but can’t.

I want to play ball with the boy like my boss at work say he do with his boy. And I don’t want to not like him just cause I think my daddy didn’t like me. I wish I was more than just there. It takes more than just being there, I think.

Last night, I pushed his momma far as I could.

“It’s all right if you don’t want to ask,” she finally said about the desks. “I won’t sit here and beg you. God’ll make a way,” she said, and I could tell I had got to her.

“Girl, wait,” I said all calm and stuff. “Can I sit here and drink my goddamn beer after working all day like a goddamn slave?” I asked her without turning around.

I could hear the water boiling at that point. It was making it humid in my man cave. Felt like steam from a shower. Still, the smell of cinnamon filled the whole house. Teniola was clean and neat and that’s how she kept the house. The furniture wasn’t new—“gently used” was what the guy at the Goodwill called it when she bought it. Teniola keep plastic on it like it’s new though. The plastic thick and make a rain boot sound when I try to get comfortable on it. I can’t imagine her thinking the velvet mess of flowers is nice, but she want to preserve them and it’s more her house than it’s mine, so I keep my mouth shut most times, and slide off the couch whenever it want me to. I don’t say nothing.

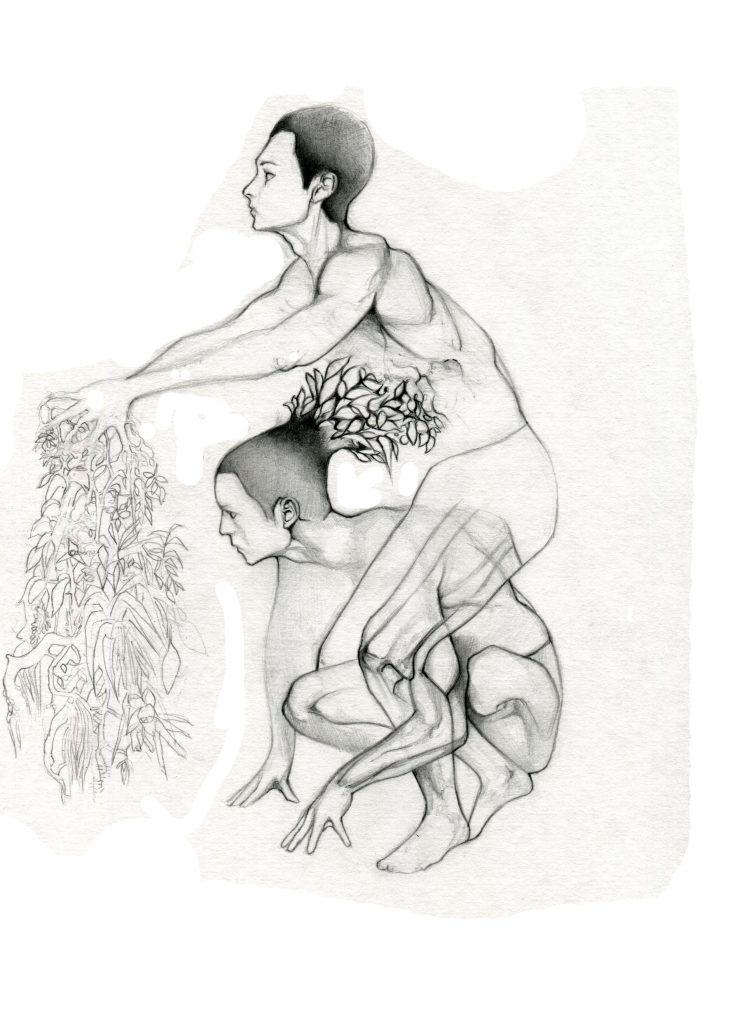

My man cave, which other folks don’t realize a man cave at all, is decorated with about seven huge fake fichus trees. Teniola started collecting them and other fake plants one-by-one when I was locked up. Got hooks hanging from the ceiling, dangling plastic ivories. Look like a jungle. Sometimes it’s hard for me to focus on the TV. Still, I set the tone of the room. That’s where I be.

“You’d do well to watch the type of language you use in my house, Rutherford,” she threw over the bar through gritted gums. And it pissed me off a little because it is just her house. I ain’t even on the lease.

The little girl step off the curb and hug my leg. I don’t know what to do—how to accept it or respond to her. I didn’t come from no affectionate home. My momma wasn’t the hugging type. Not on me anyway. She was into telling me I was gone be my daddy. On good days, my eyes reminded her of her own daddy. On good days, I saw her teeth, and the tough smiles that made her lips to part on them days, they was meant for me. She didn’t talk about my daddy, though. Never. She hated him. I guessed maybe he hit her—knocked her around or something. That’s why I ain’t never put my hands on Teniola. Well, at least fore last night.

I pat the little girl back and lie. “I missed y’all last night.” Then I think maybe it ain’t no lie. Maybe I did miss them cause it feel good to say that to her. Kind of like right.

She look up at me, still holding my leg like it belong to her. She tall for four. She’ll probably be as tall as her grandfather, Teniola’s father.

Teniola hung a picture of him in his African clothes so the kids would kind of know him. I kind of feel like I know him from the picture. It’s funny too. Even though he wearing a dress with some pants under it, he look like a real proud man in the picture. He smiling like he know who he is and don’t nothing in the world matter but that. I think Teniola still mad with him cause he went back to Africa and took a second wife. She say God only allow one woman to every man. Teniola know how to hold a grudge longer than anybody I know, but she don’t know nothing about being no man.

“For real, Daddy? You missed me for real? Him too? Did you miss him too?” She looks toward the boy. He still standing in the middle of the yard. He watching us. He scared and confused and I understand him for the first time ever. I used to be him when my momma came home mad or rejected by a man. I was all she had, so all her pain came out on me. Maybe he should be afraid of me.

I close the trunk so they can’t see inside it, but I don’t close it all the way. I want to keep it open a little because what I have to do must be done. What I feel like don’t matter.

“Why you close the trunk, Daddy?” the little girl ask. “Hope you’re not hiding Christmas presents because that’s not a real day anymore.” I shake my head at her, kind of wishing Christmas presents was what I was hiding. If that was it, I’d be winning. I’d be able to hold on to all of myself—the pain and anger from my momma and prison and life.

I bend down on one knee so I can look in her eyes. The ground cold. I can feel the sting of it through my jeans. I wonder if the little girl’s ears stinging from the chill like mine. I can feel her brother coming closer to us, but I don’t look up. I keep pretending he not there.

My daughter got a lazy eye like mine and this is the first time I noticed it. She got her momma’s skin and face, but she got big brown eyes just like me. I can’t help but smile. My eyes was a lot of pain when I was young. I got called everything from Quasimodo to One-Eyed-Willie, but as soon as I got older, the girls started loving it.

I feel like I’m looking at myself. I slowly move my hand to her face, barely touching her cheek with my thumb. Her face soft like new sheets or something. When I put my thumb over the lid of the lazy eye, she close both her eyes, almost asking me to rub the lids of them. I feel like I’m really seeing her through my fingers. She something new to me.

“It’s my best thing,” she say, and her voice bring me back to the cold. I pull my hand away from her face.

“Why’d you stop, Daddy?” she ask. “It’s my best thing. Just like yours,” she say, reaching her hand out to touch my face. I jerk my head back, away from her finger, and she pause. The corners of her mouth twitch, and she try to touch me again.

“I ain’t looked at you in a long time,” I say. I feel ashamed of that.

“Close your eyes, Daddy,” she says. “Just do what I did,” she command, sounding like a young Teniola.

I obey her because it seem like she know what she doing. Her fingers hard and cold against my skin and I feel bad about the extra money I didn’t give her momma for winter coats and gloves.

“I think Momma’s right,” she say. “I think yours is pretty just like mine.”

My eyes open and she’s smiling. The boy standing a few feet away from us. He take his eyes off me when I open mine. I know why he don’t want to look at me. I made things bad between us.

He saw what happened last night. Saw me go too far.

“Who gone let you teach they kids? Why all these people trusting you? You ain’t even finish the program you started.” I said to Teniola, trying to cut her low.

“I do a lot of reading and researching, Rutherford,” she said, defensively. “Maybe I didn’t get that paper with my name printed across the top, but I never stopped learning. I’ll never stop.”

“I guess I don’t care, Teniola. I don’t give a damn if they learn or not.” I said, raising my voice. “They always was more your kids than mine. Teach them whatever the hell you want.” The sound of my voice vibrated like a lion roaring. Tears welled up in her eyes, and I felt like a man. I heard a set of footsteps coming up the hallway and I knew one of the kids was headed to the kitchen. But I didn’t care. I was winning. The man in me was alive. “I’m just here cause I ain’t got no pl—”

“That is enough,” she said. Her voice was shaking and her lips was quivering. “You’ve said enough.” And then she picked up the dishrag from the counter and started wiping the clean surface.

“I say when it’s enough,” I said, jabbing my index finger at my chest. “That’s my job. I’m a man.”

She shook her head like she was sad but didn’t say nothing. Her eyes moved to the hallway, where the boy was standing, and she smiled a weak smile for him.

“And you gone get all these goddamn plants out of my den,” I said, still feeling a rush and wanting more than her tears as my victory.

Her eyes shifted back to me and she shook her head again. “Our son is watching, Rutherford. Show him you’re a man. Show him a man, Rutherford,” she said in a shaky voice.

“I am a man,” I screamed, slamming the palm of my hand against my chest and letting spit spray from my lips. I looked at the boy and felt a small lump in my throat. He was watching me. And right then, I hated him for it. He had been watching me for a long time. Watching me lose.

My eyes starting dancing from him to his momma, and my heart started beating like it did the first time I ever got locked up. I rocked on my feet, trying to understand what I was feeling. When tears began to burn my eyes like pebbles of rock salt, I knew I couldn’t just stand there no more. Wasn’t no way they was gone see me cry. A second later it seemed I was gone smash into Teniola. I rushed her without a plan, and like a trapped animal she threw out her hands as a shield. I think she expected me to hit her. But I didn’t. I reached out my hands and grabbed her neck, wrapping my hands around it as tight as I could.

I was pressing my thumbs so deep in her throat, her eyes was looking like they was gone pop right on out the sockets. I could see the fear in them. Just when I thought I was gone kill her, a deep scream grabbed me away from her. By the time, I looked over my shoulders to the hallway, the boy was standing there with his lips clamped tight together in an angry pout. His chest was rising and falling real heavy. He looked like the picture of Teniola daddy. That boy looked me dead in the eyes and said in an even voice, “Show me a man, Rutherford. Be a man.”

And just like that, I released my grip and Teniola and she dropped to the floor coughing and gagging while me and the boy just stood there looking at each other. I could see hunger and boldness in his eyes. It made me nervous. I looked away first—back down at his momma. Offered her my hand to get up.

She swatted it away and coughed out, “Get out of my house or I’ll call the police.”

I looked back at the boy. His lips was still clamped together. He was mad. Silent. He nodded his head toward the door. I nodded back at him and said, “Okay, boy. Okay.”

“Come here,” I say to him, standing up on my feet and lifting the trunk of the car.

He don’t want to. I can tell. It was the fear that made him bold yesterday, I think. I understand that kind of thing. Today he a boy again. I been him before. Maybe I can help him with that.

“I ain’t gone hurt you. Come on, son,” I say as nice and gentle as I can.

I lift the small desk out of the trunk and put it on the ground. He stand there looking at it like it just dropped out the sky or something. By the time I put the small chair on the ground, he trying to figure out how to lift the desk.

“Like this,” I say, bending to show him how to lift the desk right. “Always bend when something is bigger than you, son,” I say.

He nod his head back at me to show me he understand. I watch him lift it a little and struggle to get it up the curb. Once he make it past that point, he carry it with no problem. It make me feel proud like I’m a success or something.

“I’ll get this, Daddy,” my daughter say, reaching for the chair. I don’t want to turn my head away from my son. He carrying something I taught him to carry and I kind of want to hold on to that.

I swallow real hard and turn to my daughter. “Nawh, baby girl,” I say, smiling at her. “This here man work.”

LaToya Watkins is the author of Perish. Her writing has appeared in A Public Space, The Sun, Kweli Journal, McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern, Kenyon Review, The Pushcart Prize Anthology, and elsewhere. She is a Kimibilo fellow and has received support from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, MacDowell, OMI: Arts, Yaddo, Hedgebrook, and the Camargo Foundation. Her first story collection, Holler, Child, will be published in 2023. www.latoyawatkins.com